The Paris Convention for the protection of Industrial Property was adopted on March 20, 1883. The treaty marked a significant turning point in intellectual property development as it was one of the first intellectual property treaties of its kind. Notably, almost 140 years later the treaty is still in force.

One reason why the Paris Convention has stood the test of time is that it applies to intellectual property protection in a broad sense. The treaty's application covers patents, trademarks, industrial design, utility models, service marks, trade names, geographical indications, and the repression of unfair competition.

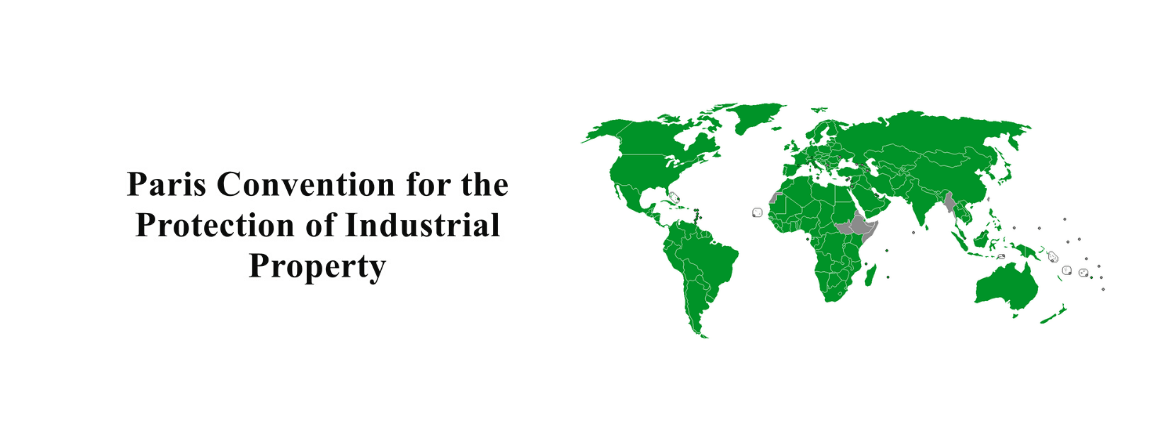

Another reason why the treaty remains significant is that the Paris Convention for Intellectual Property was the first step towards intellectual property protection not only in the country of origin but also in other countries. When the treaty was initially signed, only eleven countries agreed to participate in this noble endeavor. Today, it is easier to ask which countries are not part of the treaty rather than attempting to identify all the participants. At the time of writing, there are 176 countries recorded as signatories to the treaty.

The treaty also pioneered the concept of intellectual property priority rights. The idea of priority rights is that intellectual property rights holders can apply for IP protection for trademarks, patents, designs, and more across jurisdictions using the date of the original application.

Paris Convention History

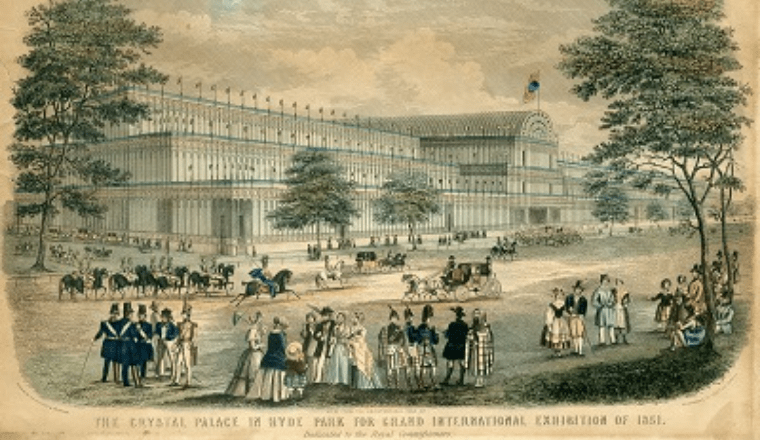

An important provision included in the Paris Convention was the requirement that its signatories "grant temporary protection to patentable inventions, utility models, industrial designs, and trademarks, in respect of goods exhibited at official or officially recognized international exhibitions held in the territory of any of them,” according to WIPO.

In fact, this provision dated back to the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The Great Exhibition 1851

The 1851 Great Exhibition held in London was an opportunity for nations to showcase the works of their designers and inventors. It was also an opportunity for the public to learn through looking. Unbridled access to exclusive foreign products, before their arrival in the host nation’s market, gave rise to the risk of piracy. Such reasoning led to the quick passing of the Protection of Inventions Act in the same year, with no discrimination on the grounds of nationality.

The protection allowed for unpatented inventions to be on display in Britain, at an exhibition previously certified by the Lords of the Committee of Privy Council for Trade and Foreign Plantations. However, the protection only lasted a year, leading critics to question the need for this temporary form of protection. Nonetheless, the exhibitors made widespread use of the protection during the Great Exhibition. In fact, 691 applications were made with 630 certificates of protection being granted.

A large number of issued certificates was far beyond the Protection of Invention Act creators’ expectations. The provisional protection offered by the 1851 Act was adopted as a general base for the British patent law in 1852. Provisional protection of a similar nature was also later adopted by other nations to make use of during their own international exhibitions and trade shows. For example Paris (1855 and 1857), London (1862), and Vienna (1873).